Registers in Modern x86-64 CPUs

Design, Function, and Data Flow

1 Registers in Modern x86-64 CPUs

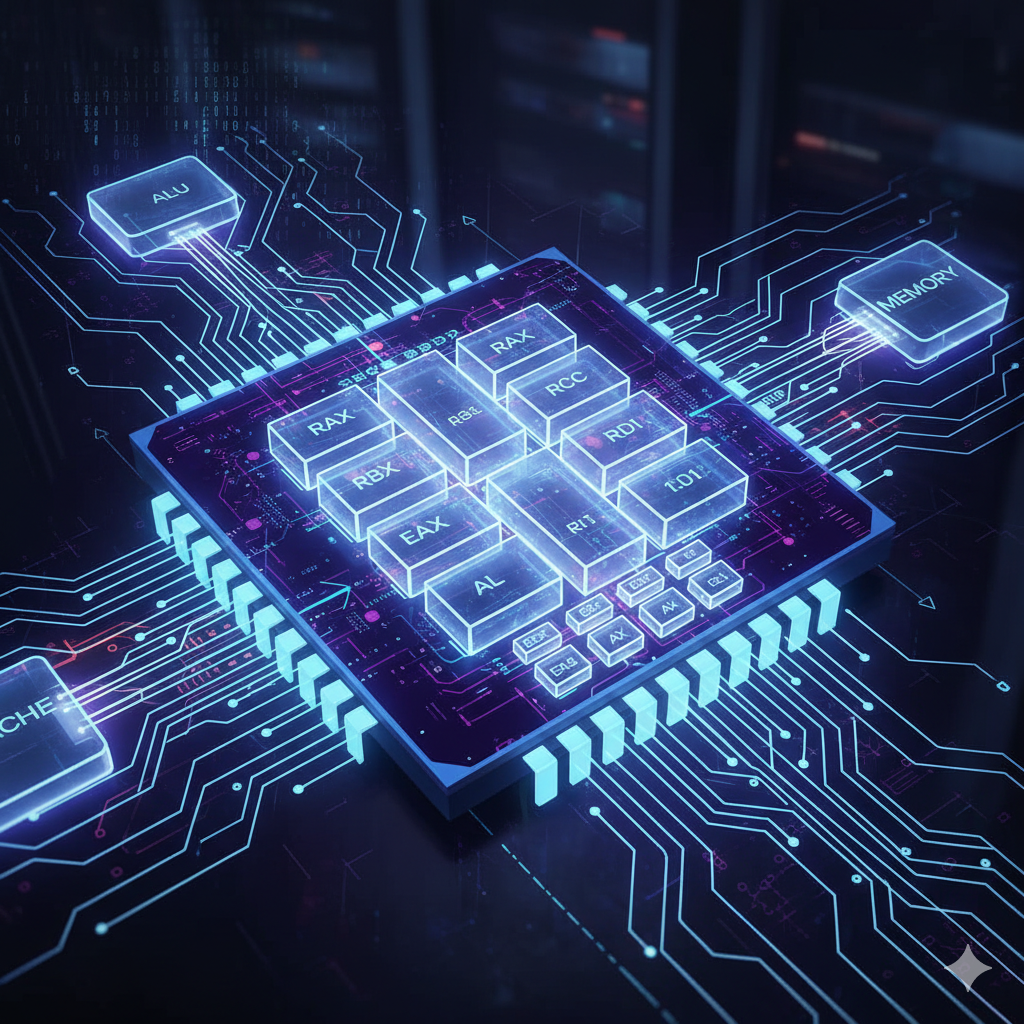

The x86-64 (or AMD64/x64) architecture significantly extends its 32-bit predecessor (IA-32), primarily by increasing the general-purpose register (GPR) count from 8 to 16 and extending their width to 64 bits. Registers are the fastest form of storage available to the CPU, acting as scratchpads for active data and addresses, which is crucial for maximizing performance.

64-bit General-Purpose Registers (GPRs)

The 16 GPRs are the most frequently used registers for arithmetic, logic, and addressing operations. They are named starting with ‘r’, where the original 8 registers from the x86 architecture are extended, and 8 new registers (R8-R15) are introduced.

| 64-bit Register | Traditional/Conventional Use (System V ABI) | Lower 32-bit | Lower 16-bit | Lower 8-bit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

%rax |

Accumulator, Return Value | %eax |

%ax |

%al |

%rbx |

Callee-Saved (Local Variable) | %ebx |

%bx |

%bl |

%rcx |

4th Argument, Counter | %ecx |

%cx |

%cl |

%rdx |

3rd Argument, Data | %edx |

%dx |

%dl |

%rsi |

2nd Argument, Source Index | %esi |

%si |

%sil |

%rdi |

1st Argument, Destination Index | %edi |

%di |

%dil |

%rsp |

Stack Pointer (Callee-Saved) | %esp |

%sp |

%spl |

%rbp |

Base Pointer (Callee-Saved) | %ebp |

%bp |

%bpl |

%r8 |

5th Argument | %r8d |

%r8w |

%r8b |

%r9 |

6th Argument | %r9d |

%r9w |

%r9b |

%r10 |

Temporary (Caller-Saved) | %r10d |

%r10w |

%r10b |

%r11 |

Temporary (Caller-Saved) | %r11d |

%r11w |

%r11b |

%r12 |

Callee-Saved (Local Variable) | %r12d |

%r12w |

%r12b |

%r13 |

Callee-Saved (Local Variable) | %r13d |

%r13w |

%r13b |

%r14 |

Callee-Saved (Local Variable) | %r14d |

%r14w |

%r14b |

%r15 |

Callee-Saved (Local Variable) | %r15d |

%r15w |

%r15b |

Register Naming Convention Hierarchy

The naming convention in x86-64 is derived from historical x86 nomenclature, indicating both the register’s size and, for legacy registers, its historical function.

64-bit (R-prefix): All 16 GPRs begin with the ‘R’ prefix (e.g.,

%rax,%rdi,%r8).32-bit (E-prefix or D-suffix): The lower 32 bits of the original 8 registers use the ‘E’ prefix (e.g.,

%eax,%edi). The newer registers (R8-R15) simply append ‘d’ (for doubleword, 32 bits) (e.g.,%r8d).16-bit (No prefix or W-suffix): The lower 16 bits of the original 8 registers use no prefix (e.g.,

%ax,%di). The newer registers append ‘w’ (for word, 16 bits) (e.g.,%r8w).8-bit (L/H or B suffix):

For the first four registers (

%rax,%rbx,%rcx,%rdx), the lowest byte uses ‘L’ (%al) and the second lowest byte uses ‘H’ (%ah).For the remaining legacy registers (

%rsi,%rdi,%rsp,%rbp) and all new registers (%r8-%r15), the lowest byte uses the ‘B’ suffix (e.g.,%sil,%r8b).

The legacy names (Accumulator, Base, Counter, Data, Source Index, Destination Index) are still reflected in the names %rax, %rbx, %rcx, %rdx, %rsi, and %rdi. The new registers (%r8 through %r15) are purely numbered and do not carry historical functional significance in their names, making their sub-register naming structure simpler.

The lower-size sub-registers allow for operations on 32-bit (%eax), 16-bit (%ax), or 8-bit (%al) data without affecting the upper bits of the 64-bit register, except for 32-bit operations which zero-extend the result to the full 64-bit register. The conventional uses are part of the Application Binary Interface (ABI), which dictates how functions pass arguments and manage state across calls. Caller-saved registers must be preserved by the caller if their values are needed after a function call, while callee-saved registers must be preserved and restored by the called function if it uses them.

Prevalence and Architectural Context

The x86-64 architecture is the undisputed standard for modern personal computing and high-performance data centers.

Dominant Implementers: The architecture is primarily implemented by Intel (under the name Intel 64 or EM64T) and AMD (who originally developed it as AMD64). Virtually every modern server, desktop, and standard laptop manufactured by these companies uses this instruction set. Its widespread adoption is due to its deep ecosystem, powerful performance characteristics, and seamless backward compatibility with legacy x86 (32-bit) software.

Architectural Contrast (Non-x86-64): The main rival to x86-64 today is the ARM architecture. ARM-based chips are designed for power efficiency and use a Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC) model, contrasting with x86-64’s Complex Instruction Set Computing (CISC) model.

ARM Dominance in Mobile: ARM has long dominated mobile devices (smartphones, tablets) due to its superior performance-per-watt ratio. Notable chipmakers using ARM include Qualcomm and Nvidia.

Apple’s Silicon Transition: A highly significant shift occurred when Apple migrated its entire Mac lineup from Intel’s x86-64 architecture to their proprietary Apple Silicon chips (starting with the M1 series). These chips, including the M2 and M3, are based on the ARM architecture (specifically AArch64). This transition was motivated by the ability to achieve tighter hardware-software integration, resulting in massive gains in energy efficiency and overall performance, particularly in laptops where thermal constraints are critical. This move represents the most high-profile challenge to x86-64’s dominance in the desktop market in decades.

Special Purpose Registers

Beyond the GPRs, the CPU relies on several critical specialized registers:

%rip(Instruction Pointer): A 64-bit register that holds the address of the next instruction to be executed. Its value is implicitly updated by the CPU. x86-64 supports RIP-relative addressing, where memory addresses are calculated as an offset from the current instruction pointer.%rflags(Status/Condition Codes): A 64-bit register storing various flags that reflect the result of an arithmetic or logical instruction, used for conditional jumps and other control-flow operations. Key flags include:ZF (Zero Flag): Set if the result is zero.

SF (Sign Flag): Set if the result is negative (most significant bit is 1).

CF (Carry Flag): Set if an arithmetic operation resulted in a carry-out or borrow-in (for unsigned arithmetic).

OF (Overflow Flag): Set if an arithmetic operation resulted in a signed integer overflow.

Other Register Types (Privileged)

These registers are primarily used by the operating system kernel and system software:

Control Registers (

CR0-CR4,CR8): Determine and manage CPU operating modes and features (e.g., enabling protected mode, paging, cache control). They are usually only accessible at the highest privilege level (ring 0).Segment Registers (

CS,SS,DS,ES,FS,GS): While segmentation is largely bypassed in x86-64’s Long Mode for a flat memory model (where segment base addresses are generally zero), the%fsand%gsregisters retain functionality to point to a base address for structures like Thread-Local Storage (TLS), providing a convenient way to access per-thread or per-CPU data.

Example Assembly: Data Flow from Memory to Register and Back

The following assembly (using AT&T syntax, typical on Linux/Unix systems) demonstrates a simple memory-to-register-operation-to-memory data flow. The goal is to load a 64-bit value from memory, increment it, and store the result back.

.section .data

; Define a 64-bit variable in the data section

my_qword: .quad 0x1234567890ABCDEF

.section .text

.global \_start

\_start:

; 1. Data Flow: Memory to Register

; Load the 64-bit value from the 'my_qword' memory address into the %rax register.

; (%rip) is used for RIP-relative addressing to find the data label.

movq my_qword(%rip), %rax

; At this point, %rax contains 0x1234567890ABCDEF

; 2. Operation on Register Data

; Increment the value in %rax by 1 (an arithmetic operation)

incq %rax

; %rax now contains 0x1234567890ABCD00 (due to carry)

; 3. Data Flow: Register to Memory

; Store the modified 64-bit value from %rax back into the 'my_qword' memory address.

movq %rax, my_qword(%rip)

; (Standard exit sequence follows, not shown for brevity)In this example:

Memory \(\rightarrow\) Register (

movq my_qword(%rip), %rax): The value is fetched from the memory address specified bymy_qword(resolved relative to%rip) and loaded into the%raxregister. This utilizes the Accumulator Register for data manipulation.Register Operation (

incq %rax): The operation is performed entirely within the high-speed register file, demonstrating the CPU’s core function.Register \(\rightarrow\) Memory (

movq %rax, my_qword(%rip)): The final result is written back from%raxto the original memory location, completing the cycle. This demonstrates the register’s role as the high-speed intermediary between memory and the Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU).

The architecture’s large and numerous registers minimize the need to constantly load and store data to and from slower memory, a concept known as register pressure reduction, which is a primary reason for x86-64’s performance gains over its 32-bit predecessor.