graph TD

A["CPU Generates Virtual Address (VA)"] --> B{"MMU Splits VA"};

B --> C["Virtual Page Number (VPN)"];

B --> D[Offset];

C --> E{"MMU Checks TLB"};

E -- TLB Hit (Fast) --> H[TLB Provides PPN];

E -- TLB Miss (Slow) --> F["Access Page Table in RAM (via PTBR)"];

F --> G["Retrieve Page Table Entry (PTE)"];

G --> H;

H --> I["Combine PPN + Offset"];

I --> J["Physical Address (PA) Generated"];

style A fill:#a2c4e0,stroke:#333

style J fill:#a2e0c4,stroke:#333

style E fill:#f9d976,stroke:#333

style H fill:#d9f976,stroke:#333

Operating System Memory Management

Virtualization and Protection

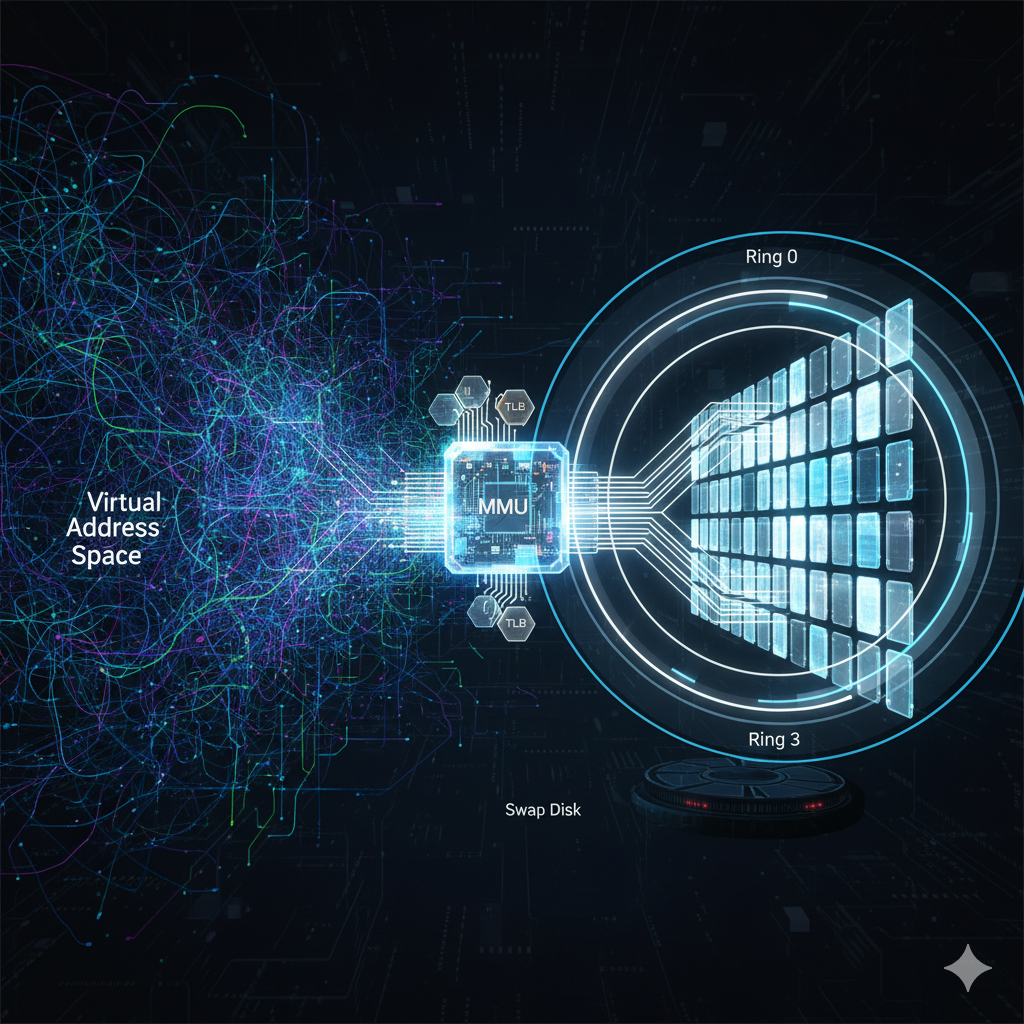

Modern computing relies on the illusion of limitless, isolated, and contiguous memory for every running program. This illusion, meticulously crafted by the Operating System (OS) and enforced by hardware, is achieved through Virtual Memory. This deep dive explores the core concepts of virtual addressing, the mechanisms of address translation, and the hardware-supported safeguards that ensure system integrity.

1 1. Virtual Memory: The Illusion of Infinity

Virtual memory is an abstraction layer that decouples a program’s perception of memory (the Virtual Address Space, or \(\text{VAS}\)) from the physical memory available in the system (Physical RAM).

1.1 The Necessity of Virtualization

Isolation (Protection): The most critical function. Each process operates within its own private \(\text{VAS}\). This isolation means that Process A, with its virtual address \(\text{0x1000}\), cannot directly access the memory of Process B, even if Process B also uses the virtual address \(\text{0x1000}\). The OS ensures that any attempt by a user-space process to access a memory location outside its assigned \(\text{VAS}\) results in a hardware fault.

Relocation: Since the OS manages the mapping, a process’s code and data can be loaded anywhere in physical RAM. Furthermore, the process does not need to be contiguous; its parts can be scattered across disparate physical locations, simplifying dynamic memory allocation and fragmentation management.

Efficiency and Sharing: Virtual memory allows multiple processes to share common read-only components, such as shared libraries or the OS kernel itself, by mapping the same physical page frame into multiple \(\text{VAS}\) at different virtual addresses.

2 2. Address Translation: Paging and the TLB

The core task of memory management is the dynamic translation of a Virtual Address (VA) generated by the CPU into a Physical Address (PA) recognized by the RAM controller. This task is performed by the Memory Management Unit (MMU), a dedicated hardware component often integrated into the CPU.

2.1 Paging

Paging is the dominant form of address translation today, relying on fixed-size blocks:

Virtual Pages: Uniform-sized blocks (e.g., 4KB) that make up the \(\text{VAS}\).

Physical Page Frames: Uniform-sized blocks in physical RAM, matching the size of virtual pages.

Page Table: A data structure maintained by the OS for each running process, typically stored in physical memory. It contains a list of entries (Page Table Entries, or \(\text{PTEs}\)) that map a Virtual Page Number (\(\text{VPN}\)) to a Physical Page Frame Number (\(\text{PPN}\)).

The address translation process is efficient and deterministic:

The CPU generates a \(\text{VA}\).

The \(\text{VA}\) is split into the \(\text{VPN}\) and a fixed offset.

The \(\text{MMU}\) uses the \(\text{VPN}\) as an index into the current process’s Page Table. The base address of the table is stored in a dedicated hardware register, like the Page Table Base Register (\(\text{PTBR}\)).

The corresponding \(\text{PTE}\) yields the \(\text{PPN}\).

The \(\text{PPN}\) is combined with the original offset to generate the final \(\text{PA}\).

This lookup process, which includes the \(\text{TLB}\) check, is summarized below:

This lookup process requires a memory access just to perform the translation before the intended data access. To mitigate this significant overhead, a crucial caching mechanism is employed: the Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB).

2.2 The Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

The \(\text{TLB}\) is a small, fast, hardware-managed associative cache located inside the \(\text{MMU}\). It stores the most recently used \(\text{VPN}\)-to-\(\text{PPN}\) translations.

When a \(\text{VA}\) is generated, the \(\text{MMU}\) first checks the \(\text{TLB}\).

TLB Hit: If the mapping is found (\(\text{TLB}\) Hit), the \(\text{PA}\) is generated instantly, avoiding the two full memory accesses (one for the \(\text{PTE}\), one for the data).

TLB Miss: If the mapping is not found, the \(\text{MMU}\) must access the Page Table in main memory. Once the \(\text{PTE}\) is retrieved, the translation is performed, and the new mapping is loaded into the \(\text{TLB}\) for future use.

2.3 Contrast with Segmentation

Segmentation is a less common memory management technique that organizes memory into variable-sized logical units (segments) corresponding to code, data, and stack. While segments align well with the logical structure of a program, their variable size leads to complex management, internal fragmentation, and difficulty handling dynamic growth, making pure paging the preferred modern approach.

3 3. Handling Scarcity: Swapping, Paging to Disk, and Thrashing

Physical memory is finite. When the total memory demanded by active processes exceeds the available physical RAM, the OS must employ mechanisms to reclaim resources, typically by utilizing secondary storage (disk).

3.1 Paging to Disk (The Modern Approach)

The \(\text{PTE}\) includes a Valid/Invalid bit. If a process attempts to access a virtual page whose \(\text{PTE}\) is marked invalid, a Page Fault interrupt is generated. The OS kernel’s Page Fault handler then:

Determines if the page is currently on disk (in the swap space) or if the memory access was illegal.

If it is on disk, the OS selects a page frame in physical RAM (using a replacement algorithm like Least Recently Used, \(\text{LRU}\)).

The contents of the chosen physical page frame are written back to disk if they are “dirty” (modified).

The required page is loaded from disk into the newly freed physical page frame.

The \(\text{PTE}\) is updated, and the instruction that caused the fault is restarted.

3.2 Thrashing

When a system attempts to run more processes than the physical memory can comfortably support, the OS spends the majority of its time servicing page faults and moving data between RAM and disk. This state is known as Thrashing.

Thrashing occurs when the collective “working set” (the minimum set of pages a process needs to operate effectively at any given moment) of all running processes exceeds the size of physical memory. The performance collapses due to the high latency of disk \(\text{I/O}\) dominating CPU execution time.

4 4. Hardware Enforcement: Protection Rings

Virtual memory provides isolation, but hardware protection features are needed to prevent a compromised user process from maliciously or accidentally corrupting the kernel or accessing privileged resources.

The modern x86 architecture uses Protection Rings, a hierarchical structure of privilege levels, where Ring 0 is the most privileged, and Ring 3 is the least.

Ring 0 (Kernel Space): The OS kernel operates here. It has unlimited access to the \(\text{MMU}\), \(\text{I/O}\) devices, and all physical memory.

Ring 3 (User Space): User applications operate here. They are restricted to their own \(\text{VAS}\) and cannot directly execute privileged instructions (like changing the \(\text{PTBR}\) or performing disk \(\text{I/O}\)).

4.1 Memory Access Control

Protection is enforced by the \(\text{MMU}\) using the \(\text{PTE}\)s:

Protection Bits: Each \(\text{PTE}\) contains bits that specify access permissions: Read, Write, Execute, and User/Supervisor mode.

MMU Check: Whenever the CPU attempts a memory operation, the \(\text{MMU}\) checks the current privilege level of the CPU against the protection bits in the \(\text{PTE}\).

If a Ring 3 process tries to write to a page marked Read-Only, or if it tries to access a page reserved for the Supervisor (Kernel), the \(\text{MMU}\) immediately triggers a hardware exception (a \(\text{Segmentation Fault}\) or \(\text{General Protection Fault}\)), transferring control back to the kernel to terminate the offending process.

By combining the abstraction of Virtual Memory with hardware-enforced protection rings, the operating system successfully creates a robust, secure, and scalable environment where numerous, complex applications can execute concurrently without interference.